Esta fue una entrevista que hizo hace unos días Richard Corliss, el reconocido crítico de la revista Time, al fanático más outspoken de Bergman – Woody Allen, durante el rodaje de su más reciente película en Barcelona.

Siempre me ha causado fascinación el hecho de que aunque el arte sea un reflejo de quien lo crea, en el caso de artistas como Bergman, como dice Woody Allen, su trabajo sea diametralmente opuesto a su personalidad.

Cualquiera pensaría que Bergman, al igual que la mayoría de sus personajes, era una alma torturada por sus dudas sobre la existencia de Dios, su propósito en el mundo o el sentido de la vida, cuando en realidad era un tipo relajado y bromista que le encantaba compartir entre amigos.

He created indelible allegories of postwar man adrift without God. He was the movies' great dramatist of strong, tortured women, and the finest director of actresses. More than any filmmaker, he raised the status of movies to an art form equal to novels and plays. Yet when Ingmar Bergman died on Monday, the popular description of him was: Woody Allen's favorite director.

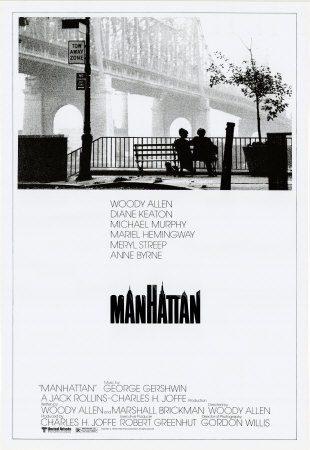

What did the domineering Swedish tragedian and the self-depreciating American comedian have in common? Plenty. Both created original scripts from their experiences and obsessions. Both worked fast — at least a movie a year for most of their long careers — and relatively cheap. Both forged long relationships with their sponsoring studios. And Bergman was a strong influence on Allen's work: from his New Yorker parody of The Seventh Seal, "Death Knocks" (in which the hero plays not chess with Death but gin rummy) to a cameo by a Grim Reaper in Love and Death and, more deeply, the inspiration for the theme and tone of Interiors and Another Woman.

Shooting his new film in Spain, Allen took time out to talk with me about Bergman. We began by remarking on the death, the same day as Bergman's, of Michelangelo Antonioni — the Italian director of L'Avventura, Eclipse, Blowup and The Passenger, and another prime depicter of modern alienation.

RICHARD CORLISS: The insular Swede and the cosmopolitan Italian, dead on the same day.

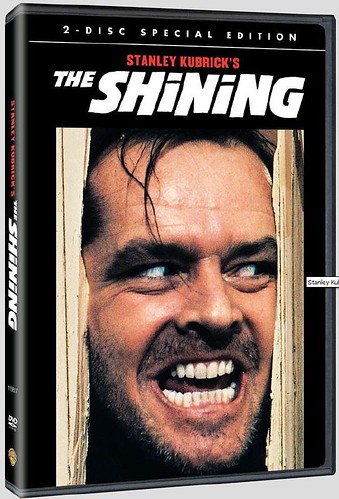

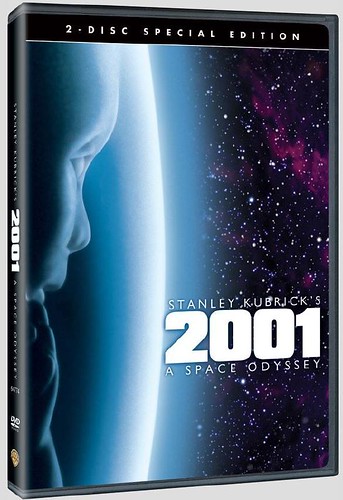

WOODY ALLEN: Dreadful and astonishing. Two titanic film directors! Everyone here was shocked. Their work lives on, which just means their films are showing in a few places and sold on DVD. But the men are no longer with us, and that is tragic.

R.C.: But Bergman was 89, Antonioni 94. They had a great run, and you have to think they got to say what they had to say.

W.A.: Yes, they were not prematurely taken from our midst. Still, to me, the fact that it happens at all is sad, just terrible, tragic.

R.C.: Your connection with Bergman is well known. Did you know Antonioni at all?

W.A.: I knew him slightly and spent some time with him. He was thin as a wire and athletic and energetic and mentally alert. And he was a wonderful ping-pong player. I played with him; he always won because he had a great reach. That was his game.

R.C.: But it's fair to say you're first and foremost a Bergman guy, and that you have been for 50 years. There were a lot of young people in the '50s who saw Bergman's films — usually it was The Seventh Seal — and were overwhelmed with an almost religious conversion. And the doctrine of this religion was that film was an art.

W.A.: I agree. For me it was Wild Strawberries. Then The Seventh Seal and The Magician. That whole group of films that came out then told us that Bergman was a magical filmmaker. There had never been anything like it, this combination of intellectual artist and film technician. His technique was sensational.

R.C.: After long admiring Bergman, you finally met him, through Liv Ullmann, who had starred in many of his films and lived with him for a few years.

W.A.: He and I had dinner in his New York hotel suite; it was a great treat for me. I was nervous, I really didn't want to go. But he was not at all what you might expect: the formidable, dark, brooding genius. He was a regular guy. He commiserated with me about low box-office grosses and women and having to put up with studios.

Later, he'd speak to me by phone from his oddball little island [Faro, where Bergman lived his last 40 years]. He confided about his irrational dreams: for instance, that he would show up on the set and not know where to put the camera and be completely panic-stricken. He'd have to wake up and tell himself that he is an experienced, respected director and he certainly does know where to put the camera. But that anxiety was with him long after he had created 15, 20 masterpieces.

R.C.: You knew he was Ingmar Bergman, but maybe he didn't. He didn't get to view his reputation from the outside.

W.A.: Exactly. The world saw him as a genius, and he was worrying about the weekend grosses. Yet he was plain and colloquial in speech, not full of profound pronunciamentos about life. Sven Nykvist [his cinematographer] told me that when they were doing all those scenes about death and dying, they'd be cracking jokes and gossiping about the actors' sex lives.

R.C.: You worked with Nykvist on four films. And you seem to share Bergman's work ethic.

W.A.: I copied some of that from him. I liked his attitude that a film is not an event you make a big deal out of. He felt filmmaking was just a group of people working. At times he made two and three films in a year. He worked very fast; he'd shoot seven or eight pages of script at a time. They didn't have the money to do anything else.

W.A.: I copied some of that from him. I liked his attitude that a film is not an event you make a big deal out of. He felt filmmaking was just a group of people working. At times he made two and three films in a year. He worked very fast; he'd shoot seven or eight pages of script at a time. They didn't have the money to do anything else.

R.C.: One reason that boys of a certain age were enthralled by Bergman's films was that he had some of the world's most beautiful and powerful actresses in his repertory company: Eva Dahlbeck, Harriet and Bibi Andersson, Ingrid Thulin, Gunnel Lindblom, Liv Ullmann, Lena Olin. These were major mesmerizers, and they all worked for him.

W.A.: He was obsessed with faces and had a wonderful way with women. He had an affinity for women that Tennessee Williams did. Some kind of closeness he felt. Their problems obsessed him.

R.C.: One difference there is that Tennessee Williams didn't sleep with his leading ladies. Bergman was a famously imperious charmer, and had long liaisons with Harriet Andersson, then Bibi Andersson, then Liv Ullmann. There was a rumor that all seven actresses in his film All These Women were former Bergman mistresses.

W.A.: That would not surprise me because, as I heard it from Sven, that's the way it was there. There was an enormous amount of socializing, and sexual and romantic escapades. It was a lighter situation than you would think. There's so much feeling on the screen that you think he had to have a serious life. But he was a ladies' man. He loved relationships with women.

R.C.: Many film critics assign Bergman to a lower rank because, they say, he makes filmed plays. I don't see this as a limitation, but wouldn't you agree that he was essentially a film writer who directed his own work?

W.A.: That could be said of me too. But you must also take a Bergman film like Cries and Whispers where there's almost no dialogue at all. This could only be done on film. He invented a film vocabulary that suited what he wanted to say, that had never really been done before. He'd put the camera on one person's face close and leave it there, and just leave it there and leave it there. It was the opposite of what you learned to do in film school, but it was enormously effective and entertaining.

R.C.: OK. So you think he's great, and I think he's great. But to many  young people — I mean bright, film-savvy kids — he's Ingmar Who? What relevance do his films have today?

young people — I mean bright, film-savvy kids — he's Ingmar Who? What relevance do his films have today?

W.A.: I think his films have eternal relevance, because they deal with the difficulty of personal relationships and lack of communication between people and religious aspirations and mortality, existential themes that will be relevant a thousand years from now. When many of the things that are successful and trendy today will have been long relegated to musty-looking antiques, his stuff will still be great.

R.C.: But not many artists worry about God's silence these days. In the media the current battle is between militant believers and devout atheists. You get very few tortured agnostics.

W.A.: You're right. That was his obsession. He was brought up religiously [his father was a Lutheran minister] and it wasn't simply a question of atheism or not. He longed for the possibility of religious phenomenon. That longing tortured him his whole life. But in the end he was a great entertainer. The Seventh Seal, all those films, they grip you. It's not like doing homework.

R.C.: If someone who hadn't seen any of his films asked you to recommend just five, what would be your Bergman starter set?

W.A.: The Seventh Seal, Wild Strawberries, The Magician, Cries and Whispers and Persona.

R.C.: Many directors would be happy to have made just those five films.

W.A.: Or one of them.

En Jeopardy, llamada en muchos países Astucia de Mujer, Barbara Stanwyck hace precisamente de una mujer que debe utilizar su astucia para salvar a su marido y salvarse ella misma.

En Jeopardy, llamada en muchos países Astucia de Mujer, Barbara Stanwyck hace precisamente de una mujer que debe utilizar su astucia para salvar a su marido y salvarse ella misma. Seven logra mantener tensión y angustia constantes en sólo 70 minutos. La película no cae en ningún momento, un gran logro para este género.

Seven logra mantener tensión y angustia constantes en sólo 70 minutos. La película no cae en ningún momento, un gran logro para este género.  mejores y más emblemáticos directores de la historia del cine.

mejores y más emblemáticos directores de la historia del cine.

Si tuviera que hacer una lista de las mejores vaqueradas que he visto, esta sería una.

Si tuviera que hacer una lista de las mejores vaqueradas que he visto, esta sería una.

W.A.: I copied some of that from him. I liked his attitude that a film is not an event you make a big deal out of. He felt filmmaking was just a group of people working. At times he made two and three films in a year. He worked very fast; he'd shoot seven or eight pages of script at a time. They didn't have the money to do anything else.

W.A.: I copied some of that from him. I liked his attitude that a film is not an event you make a big deal out of. He felt filmmaking was just a group of people working. At times he made two and three films in a year. He worked very fast; he'd shoot seven or eight pages of script at a time. They didn't have the money to do anything else.  young people — I mean bright, film-savvy kids — he's Ingmar Who? What relevance do his films have today?

young people — I mean bright, film-savvy kids — he's Ingmar Who? What relevance do his films have today?